10

May, 2015

10

May, 2015

Here at Sketch Corp. we’re big on numbers. You could say we “count” on them. Ha ha.

A lot of the decisions we make on a daily basis are driven, at least in part, by data. From creating marketing proposals to running Google AdWords campaigns, we rely heavily on raw numbers and statistics when choosing what course of action to take.

There is however one particular number that we’ve always been a little wary of. Not because it’s incorrect or unreliable, but because it gets talked up so much that people forget what it actually means and should be used for.

That number is Return On Investment (ROI).

Here’s the problem: ROI isn’t a magic number. It can be useful when put in the right context, but it is limited in more ways than one.

What is ROI and what does it tell us?

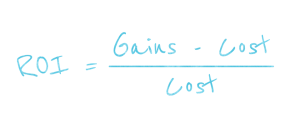

ROI is, of course, mainly useful when calculating how much you’re getting out of what you’re putting in. It tells you, in percentage terms, how much of your investment you’re earning back.

Let’s say we’re investing in some shares. We buy 100 shares at $50 each, making a total investment of $5,000. The shares top out at $72, at which point we sell. We make $7200 in total – a quick $2200 profit.

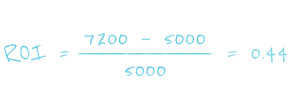

Using the equation above, our ROI is:

Our ROI is 0.44, or 44%. Not too shabby.

But herein lies a key problem with ROI. Imagine if we’d bought only 1 share, not a hundred. Our ROI would still be the same – 44% – but we would have made just $22.

ROI has only told us what percentage return we get, and nothing else.

ROI in marketing?

One of the most difficult (yet most necessary) areas where ROI is calculated and used is in marketing. But as we saw above, we can’t just plug a few numbers into an equation and think we’re getting somewhere.

A common way that businesses measure the effectiveness of their marketing is with an ROI calculation: “I spent X on all my marketing, and my sales or enquiries increased by Y, so my ROI is Z”.

Again, this can be effective if you have an extremely simple sales and marketing funnel, but as soon as you start introducing variables, it quickly becomes difficult to isolate the readings you need.

For example, a door-to-door sales company that decides to invest in a call centre to support its existing team could fairly easily calculate the ROI of their investment – the added cost of creating and running the call centre would immediately be visible in their sales figures. Simple.

But if a car manufacturer ran a social media campaign getting people to take selfies of themselves with their new vehicles in interesting places, it would probably be highly valuable brand building and at some point lead to a sale, but the ROI would be virtually impossible to measure – and if it had to be produced, it would likely be a negative percentage.

Does this mean ROI isn’t useful?

Yes and no. In some cases, ROI on its own is pointless in any kind of decision-making capacity. But in almost all cases, it’s a vital part of a larger suite of statistics that you’d be crazy not to measure.

Whatever you choose to do, the important thing is that you plan, test and measure. Over and over again.

No matter what kind of data you’re collecting, as long as you’re collecting it, you’re halfway there. The other half is sorting through the data and making educated inferences from it.

What you shouldn’t be doing is putting all your thought into one stat. If you simply swap ROI for gross revenue or total clicks you’re making the same mistake but with a different number.

We might need to go into more detail on performance measurement in a future article, but for now let’s just accept that testing and measuring is the only real way of providing the evidence you need to make decisions.

What about the immeasurable?

We’ve been going on and on about needing to measure things, but there’s another side to the coin, and it’s just as important.

No matter what kind of business you’re in, your bottom line is going to be pretty high on your list of priorities. But there are countless factors that affect your bottom line that can’t be measured.

How do you quantify the culture of your organisation? How do you show that you’re fulfilling your mission and vision? How do you put a dollar value on your brand’s reputation?

Here at Sketch Corp., we’re constantly reminded of questions like these. For every detailed Cost Per Acquisition report we provide, there’s always a brand realignment or some other immeasurable counterpart that balances it out.

An example

Here’s an example to mull over…

You run a mobile pet grooming business, with 5 vans spread across your city. At the moment, most of your work comes from newspaper ads, word of mouth, and a little bit of organic traffic hitting your website.

It’s time to expand, and to do so, you’re looking to get every van as busy as possible. You want to see how much workload is sustainable, and you want to see how much it’ll cost you to replicate your model as you grow. Once you’ve got a bit of capital saved up, you’re going to buy some extra vans and employ new operators.

You’ve been advised that you need to bump up your advertising spend, and that the most cost-effective way of gaining more traction is to redesign your website, invest in SEO, and start up a Pay Per Click campaign to target individual localities where your vans operate.

All of this costs you $20,000 over the next 4 months, at which point you try to work out the ROI of investing in your new website and online lead generation.

In total, you calculate that you made an additional $4,000 in revenue over the four-month period compared to annual averages. This equates to 20% ROI, but does this give you enough reason to continue?

What do you do next? What does this figure tell you? Do you go ahead with the expansion, or do you modify your model? What other calculations would you want to look at before deciding on a course of action?

Here’s what we’d be asking:

- Is this model scalable?

- Was the increased revenue due to the extra advertising, the improved website, or what?

- Will we need to keep our advertising spend at this level to drive leads to our new vans?

- Will this level of revenue fluctuate with annual seasonal cycles?

- How long will it take for our new vans and employees to pay for themselves?

- How much is our added exposure and brand recognition worth?

This is why we have a love/hate relationship with ROI. It’s necessary, but altogether not very useful at the same time.